As with Lars Hansen and Gene Fama, Bob Shiller has also produced a span of interesting innovative work, that I can't possibly cover here. Again, don't let a Nobel Prize for one contribution overshadow the rest. In addition to volatility, Bob did (with Grossman and Melino) some of the best and earliest work on the consumption model, and his work on real estate and innovative markets is justly famous. But, space is limited so again I'll just focus on volatility and predictability of returns which is at the core of the Nobel.

|

| Source: American Economic Review |

The graph on the left comes from Bob's June 1981

American Economic Review paper. Here Bob contrasts the actual stock price p with the "ex-post rational" price p*, which is the discounted sum of actual dividends. If price is the

expected discounted value of dividends, then price should vary less than the

actual discounted value of ex-post dividends. Yet the actual price varies tremendously more than this ex-post discounted value.

This was a bombshell. It said to those of us watching at the time (I was just starting graduate school) that you Chicago guys are missing the boat. Sure, you can't

forecast stock returns. But look at the wild fluctuations in prices! That can't possibly be efficient. It looks like a whole new category of test, an elephant in the room that the Fama crew somehow overlooked running little regressions. It looks like prices are incorporating information -- and then a whole lot more! Shiller interpreted it as psychological and social dynamics, waves of optimisim and pessimism.

(Interestingly, Steve Leroy and Richard Porter also wrote an essentially contemporary paper on volatility bounds in the May 1981 Econometrica:

The Present Value Relation: Tests Based on Implicit Variance Bounds, that has been pretty much forgotten. I think Shiller got a lot more attention because of the snazzy graph, and the seductive behavioral interpretation. This is not a criticism. As I've

said of the equity premium, knowing what you have and marketing it well matters.

Deirdre McCloskey tells us that effective rhetoric is important and she's right. Most great work emerges as the star among a lot of similar efforts. Young scholars take note.)

But wait, you say. "Detrended by an exponential growth factor?" You're not allowed to detrend a series with a unit root. And what exactly is the extra content, overlooked by Fama's return forecasting regressions? Aha, a 15 year investigation took off, as a generation of young scholars dissected the puzzle. Including me. Well, you get famous in economics for inducing lots of people to follow you, and Shiller (like Fama and Hansen) is justly famous here by that measure.

My best attempt at summarizing the whole thing is in the first few pages of "

Discount Rates," and the theory section of that paper. For a better explanation, look there. The digested version here.

Along the way I wrote "

Volatility Tests and Efficient Markets" (1991) establishing the equivalence of volatility tests and return regressions, "

Explaining the Variance of Price-Dividend Ratios" (1992), an up to date volatility decomposition, "

Permanent and Transitory Components of GNP and Stock Prices" (1994) "

The Dog That Did Not Bark" (2008), three review papers, an extended chapter in my textbook "Asset Pricing," covering volatility, bubbles and return regressions, and last but not least an economic model that tries to explain it all, "

By Force of Habit" (1999) with John Campbell. And that's just me. Read the citations in the Nobel Committe's "

Understanding Asset Prices." John Campbell's list is three times as long and distinguished.

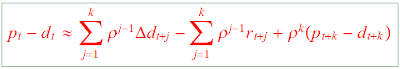

So, in the end, what do we know? A modern volatility test starts with the Campbell-Shiller linearized present value relation

Here p=log price, d=log dividend, r=log return and rho is a constant about 0.96. This is just a clever linearization of the rate of return -- you can rearrange it to read that the long run return equals final price less initial price plus intermediate dividends. Conceptually, it is no different than reorganizing the definition of return to

You can also read the first equation as a present value formula. The first term says prices are higher if dividends are higher. The second term says prices are higher if returns are lower -- the discount rate effect. The third term represents "rational bubbles." A price can be high with no dividends if people expect the price to grow forever.

Since it holds ex-post, it also holds ex-ante -- the price must equal the expected value of the right hand side. And now we can talk about volatilty:

the price-dividend ratio can only vary if expected dividend growth, expected returns, or the expected bubble vary over time. Likewise, multiply both sides of the present value identity by p-d and take expectations. On the left, you have the variance of p-d. On the right, you have the amount by which p-d forecasts dividend growth, returns, or future p-d.

The price-dividend ratio can only vary if it forecasts future dividend, growth, future returns, or its own long-run future. The question for empirical work is,

which is it? The surprising answer:

it's all returns. You might think that high prices relative to current dividends mean that markets expect dividends to be higher in the future. Sometimes, you'd be right. But on average, times of high prices relative to current dividends (earnings, book value, etc.) are not followed by higher future dividends. On average, such times are followed by lower subsequent long-run returns.

Shiller's graph we now understand as such a regression: price-dividend ratios do not forecast dividend growth. Fortunately, they do not forecast the third term, long-term price-dividend ratios, either -- there is no evidence for "rational bubbles." They do forecast long-run returns. And the return forecasts are enough to exactly account for price-dividend ratio volatility!

Starting in 1975 and continuing through the late 1980s, Fama and coauthors, especially Ken French, were running regressions of long-run returns on price-dividend ratios, and finding that returns were forecastable and dividend growth (or the other "complementary" variables) were not. So, volatility tests are not something new and different from regressions. They are

exactly the same thing as long-run return forecasting regressions. Return forecastability is exactly enough to acount for price-dividend volatility. Price-dividend volatility is another implication of return forecastability-- and an interesting one at that! (Lots of empirical work in finance is about seeing the same phenomenon through different lenses that shows its economic importance.)

And the pattern is pervasive across markets. No matter where you look, stock, bonds, foreign exchange, and real estate, high prices mean low subsequent returns, and low prices (relative to "fundamentals" like earnings, dividends, rents, etc) mean high subsequent returns.

These are the facts, which are not in debate. And they are a stunning reversal of how people thought the world worked in the 1970s. Constant discount rate models are flat out wrong.

So, does this mean markets are "inefficient?" Not by itself. One of the best parts of Fama's 1972 essay was to prove a theorem: any test of efficiency is a joint hypothesis test with a "model of market equilibrium." It is entirely possible that the risk premium varies through time. In the 1970s, constant expected returns were a working hypothesis, but the theory long anticipated time varying risk premiums -- it was at the core of Merton's 1972 ICAPM -- and it surely makes sense that the risk premium might vary through time.

So here is where we are: we know the expected return on stocks varies a great deal through time. And we know that time-variation in expected returns varies exactly enough to account for all the puzzling price volatility. So what is there to argue about? Answer: where that time-varying expected return comes from.

To Fama, it is a business cycle related risk premium. He (with Ken French again) notices that low prices and high expected returns come in bad macroeconomic times and vice-versa. December 2008 was a recent time of low price/dividend ratios. Is it not plausible that the average investor, like our endowments, said, "sure, I know stocks are cheap, and the long-run return is a bit higher now than it was. But they are about to foreclose on the house, reposess the car, take away the dog, and I might lose my job. I can't take any more risk right now." Conversely, in the boom, when people "reach for yield", is it not plausible that people say "yeah, stocks aren't paying a lot more than bonds. But what else can I do with the money? My business is going well. I can take the risk now."

To Shiller, no. The variation in risk premiums is too big, according to him, to be explained by variation in risk premiums across the business cycle. He sees irrational optimism and pessimism in investor's heads. Shiller's followers somehow think the government is more rational than investors and can and should stabilize these bubbles. Noblesse oblige.

Finally, the debate over "bubbles" can start to make some sense. When Shiller says "bubble," in light of the facts, he can only mean "time-variation in the expected return on stocks, less bonds, which he believes is disconnected from rational variation in the risk premium needed to attract investors." When Fama says no "bubble," he means that the case has not been proven, and it seems pretty likely the variation in stock expected returns does correspond to rational, business-cycle related risk premiums. Defining a "bubble," clarifying what the debate is about, and settling the facts, is great progress.

How are we to resolve this debate? At this level, we can't. That' the whole point of Fama's joint hypothesis theorem and its modern descendants (the existence of a discount factor theorems). "Prices are high, risk aversion must have fallen" is as empty as "prices are high, there must be a wave of irrational optimism." And as empty as "prices are high, the Gods must be pleased." To advance this debate, one needs an economic or psychological model, that

independently measures risk aversion or optimisim/pessimism, and predicts when risk premiums are high and low. If we want to have Nobels in economic "science," we do not stop at story-telling about regressions.

One example: John Campbell and I (Interestingly, Shiller was John's PhD adviser and frequent coauthor) wrote such a model, in "

By Force of Habit". It uses the history of consumption and an economic model as an independent measure of time varying risk aversion, which rises in recessions. Like any model that makes a rejectable hypothesis, it fits some parts of the data and not others. It's not the end of the story. It is, I think, a good example of the kind of model one has to write down to make any progress.

I am a little frustrated by behavioral writing that has beautiful interpretive prose, but no independent measure of fad, or at least no number of facts explained greater than number of assumptions made. Fighting about who has the more poetic interpretation of the same regression, in the face of a theorem that says both sides can explain it, seems a bit pointless. But an emerging literature is trying to do with psychology what Campbell and I did with simple economics. Another emerging literature on "institutional finance" ties risk aversion to internal frictions in delegated management, and independent measures such as intermediary leverage.

That's where we are. Which is all a testament to Fama, Shiller, Hansen, and asset pricing. These guys led a project that assembled a fascinating and profound set of

facts. Those facts changed 100% from the 1970s to the 1990s. We agree on the facts. Now is the time for theories to understand those facts. Real theories, that make quantitative predictions (it is a quantiative question:

how much does the risk premium vary over time), and more predictions than assumptions.

If it all were settled, their work would not merit the huge acclaim that it has, and deserves.

Update: I'm shutting down most comments on these. For this week, let's congratulate the winners, and debate the issues some other day.